WHEN DID THE WEST’S REGIME CHANGE WARS *REALLY* START?

It is usual to think of the concept of regime change having its genesis only around a decade a half ago or so. But, thinking more deeply on this subject, is this really the case?

What are the normal justifications given for the regime change wars we have seen over these last many years?

The urge to spread freedom and democracy. In more recent times the desire to spread western liberal democracy and the adherence to what is termed a rules-based international system. But do these concepts cover all aspects of the ambitions involved, or are there other, less savoury and sanctimonious aspects to these activities of western political elites? And does the history of these rather more self-interested motivations extend further back than most of us might think?

I would argue that we should, as a certain well-known media-generated saying goes, question more… and attempt to think more deeply, extending and extrapolating out from our parameters concerning when the regime change impulse began.

It is received knowledge in the West that communism was wholly bad, without any redeeming features. Yet, when a close examination of what was built and what services were provided, at what cost and to what a degree concerning access to benefits we begin to see that it is impossible to paint in such stark, contrasting colours.

Even a short time spent looking around ex-communist bloc nations will reveal certain things. Polyclinics in even the smallest town and even villages, communal culture houses the same. Residential housing in good or reasonably good order with more than sufficient parklands surrounding or as integral features of them. Schools of all levels within easy reach of all. And these are simply the visual elements of what you cannot avoid assessing was a system that at the very least, cared to provide the basics for its people.

Then you have the social services provided where access to medicine was virtually free, as was education, and the right to a job, a home and predictability of benefits such as holidays, spa visits when needed and so on. The stability of income meant a family could be raised and those children who when old enough would receive grants to enable them to have a home, family and work of their own.

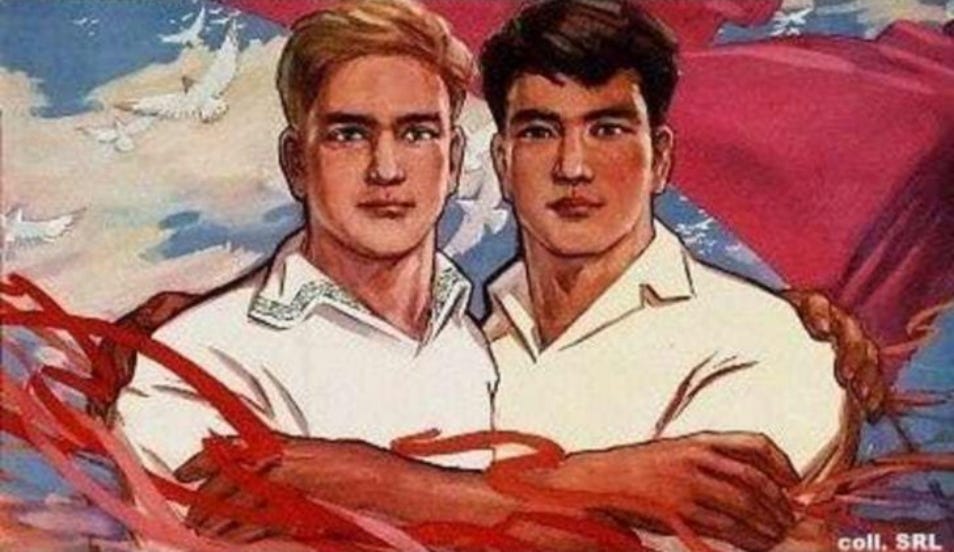

These nations had no foreign debt and were largely self-sufficient in food and much else besides due to cooperative agreement among brother and sister nations. The basics of life were provided from cradle to grave in a spirit of unity and community where the collective good of all was prioritised.

Now all this was of course not popular with everyone. Many, especially those with an artistic or intellectual bent felt restricted and in many cases hugely so. They were not free to say what they liked or create as they wished. The state, ever inclined to be protective of the overall project to look after global rather than individual rights without doubt was reduced to over reacting at times and perhaps extremely so on occasion. Believing the system they adhered to was so important that any threat to it, no matter how seemingly small and insignificant it may be, might grow and bring the whole project down, must surely have caused many if not all the abuses that clearly occurred. Other abuses were also no doubt brought about by the loss of idealism, replaced by a bureaucratic mindset, or one of egotism or simply by common sociopathic tendencies where a brutal mentality is often favoured, as in a national security services.

But to say the entire system had no worth and was wholly repressive is certainly wrong as a truly objective examination and analysis will show clearly.

The historical facts are clear regarding its demise however. The western powers dedicated themselves to its destruction in the years immediately following the end of the Second World War and continued in this endeavour until the desired result occurred in the late Eighties, early Nineties.

I would strongly argue that what we think of now as a regime change war is not a modern occurrence at all. We are generally accustomed to think of these as quite short-lived affairs and mostly linked to the ‘War on Terrorism’ post 9/11. But I would argue this is too narrow a view, too restricted in its mental focus on the immediacy we are all encouraged to embrace these days.

There is much scepticism these days regarding the very sanctimonious and self-righteous words of western political leaders of recent and current times regarding their pursuit of global ‘democracy’, ‘freedom’ and the more modern phrases concerning ‘western liberal values’ and an ‘international rules based order’ when seeking regime change. However, what do these regime change wars bring, apart from a general chaos in most cases? I would argue that they bring down systems of governance and individuals who present a challenge of some sort to western national interests.

Those national interests are spoken of by the western political elites but they are embroidered around with so much other verbiage concerning human rights, democracy and freedom that the self-interest once openly stated gets buried far down in the mix. The selling points that grab idealistic attention, prick consciences and stimulate supportive emotions are those that get emphasised.

The Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies had to be demonised just as any more recent regime change target. Nothing positive was to be said about their systems or societies, certainly not about the services, infrastructure and benefits that were provided. Does this sound familiar? It is the same with every regime change project as if from a standard playbook. Leaders need to be portrayed as virtual demons who oppress and subjugate their people and that this was a generalised state, not an exceptional one. Certainly they had ammunition to work on as with Stalin and Mao… but subjectivity overall replaced any unwanted objectivity in almost every aspect.

The communism of the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact bloc was far from perfect, there were deep flaws and it was inevitable that a sizeable minority of those who prized freedom over most other aspects of life would be unhappy and perhaps terribly so. But the goal remained idealistic within these societies even if the practicalities sometimes eluded their abilities or finances. The goal remained to provide the basics of life and then some to all, not to leave everything to the market place where random suffering or great benefit could occur along with the positives of creativity and thoughtfulness.

In total these societies were a work in progress and that progress was measured in terms of the degree that entire population of each of its nations, republics or soviets would benefit rather than continue with the us and them societies they had known previously of aristocrats and serfs, capitalist elites and their permanently lower class workers.

These were works in progress, a collective, extremely idealistic project, that due to admittedly many internal factors, but very definitely and obviously due to many external factors, came to be undermined and fell, leaving most of the world to the vagaries of the market place.

The last great unifying project may have died at that time. Though elements of the joint Russian-Chinese project we see rising now may well revive something similar, this due to a common emphasis on agreement and fairness. Only the future will show if this can be realised… or whether the regime change mentality still with us in the western world will prevail once again.